Early 1980s – Bonnie Youngerman, the Guild’s first Organ Restoration Chair

Bonnie Youngerman was the Callanwolde Guild’s first Organ Restoration Chairman. She served the Guild in this capacity from 1980 to 1984. By the end of her four-year tenture, the Callanwolde Aeolian Organ was well on its way to being fully restored.

When Bonnie was asked how she happened to join the Guild, she answered, “I came from Chicago where they tear down everything that is old. My friend Pat Ott asked me to join a group interested in preserving Callanwolde, the old Candler estate, and I said ‘yes’ without hesitation. In May 1975, when the Guild incorporated, I became a charter member.

Bonnie said she could not recall when the Guild consciously decided to restore the Aeolian Organ. However, it was apparent to everyone concerned that the organ was an integral part of the house and the house was designed for its accommodation. You could not preserve the house unless you restored the Aeolian House Organ. From the beginning, the Guild valued this one-of-a-kind instrument and welcomed the opportunity to be part of its restoration.

Although minor repairs had been made to keep the organ somewhat operational, nothing significant had been considered until 1980 when Guild President Shirley Healy asked Bonnie Youngerman to serve on her Board of Directors as Organ Restoration Chairman.

At this point, Elizabeth Elder introduced Bonnie to Charles Walker, the Callanwolde Guild’s knowledgeable Aeolian Organ Volunteer friend. Charles, in turn, suggested that Arthur Schleuter, of Pipe Organ Sales and Services in Lithonia, be consulted.

As soon as it became apparent that the restoration project was going to be quite costly, everyone began looking for ways to raise the necessary funds. Bonnie sent out over sixty letters to foundations and philanthropic organizations known to support this kind of culturally oriented preservation project. Unfortunately, these requests were never acknowledged.

Therefore, the Gift/Art Shop, staffed by Guild volunteers, became the major source of funds for the restoration. In addition, more funds were raised through the sale of the Guild’s Chem Lawn stock. Also, Guild-sponsored tours, luncheons, and special fundraisers contributed to the project.

Under Bonnie’s four-year supervision, the organ restoration project moved along at a steady pace. The starter mechanisms for both blowers were replaced. A new rectifier was placed on the organ. The static regulator above the main blower was releathered. The harp and chimes were restored and the Great Swell motor rebuilt. By the end of her four years, plans were underway to rebuild the Swell Division.

Bonnie was quick to give credit to Guild Presidents Shirley Healy, Martha Elizabeth Cornell, Carol Hale, and Jeanne Pearson for their enthusiastic support; to the women of the Guild for their untiring labors; and to the Art Shop for its many financial contributions.

Mid-Late 1980s – Mary Lynn Weatherly, the Guild’s second Organ Restoration Chair

Mary Lynn Weatherly served the Callanwolde Guild as Organ Restoration Chairman following Bonnie Youngerman’s resignation in 1984. She holds two music degrees and is a full-time music teacher, as well as a professional organist.

The mother of one of her former students introduced her to Callanwolde’s Aeolian Organ. When she saw the instrument and heard it played, she offered to become a Callanwolde Guild volunteer member and help with its restoration.

I asked Mary Lynn to explain how orchestral pipe organs, such as Callanwolde’s, developed. She answered, “In the early 1900s, symphony orchestras were virtually nonexistent in most cities and those that did exist were not the caliber of today’s orchestras. The orchestral organ was crafted by organ builders of the period to give audiences the opportunity to hear and enjoy the fullness of symphonic orchestral sounds. Wealthy families of the era, who enjoyed music in their homes, often installed such residential pipe organs. Most of these orchestral residential pipe organs were manufactured by the Aeolian Pipe Organ Company of New York.”

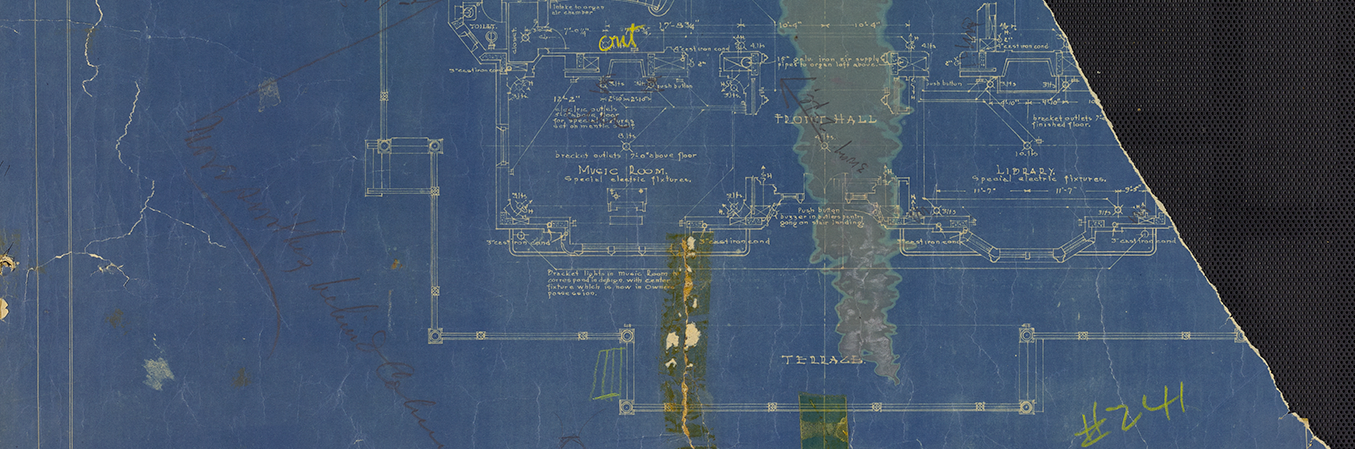

Callanwolde’s Aeolian Organ is a remarkable example of the design, engineering and craftsmanship that developed during the era of the Romantic Orchestral Organ. The instrument is controlled by a three-manual console with built-in roll player. It has seven divisions: Great Organ, Swell Organ, Choir Organ, Solo Organ, Echo Great Organ, Echo Swell Organ, and Pedal Organ. It is contained in four specially-built chambers in the house. Four parts are in two chambers over the front entrance, which play through the grill in the stone archway. The third chamber is on the third floor over the south end of the main hall and can play over the stairway or over the entry archway. The fourth chamber is on the third floor over the entrance to the billiard room and can play into the main staircase or the winter living room.

The organ contains 55 ranks (sets of pipes) for a total of 3,742 pipes. Pressurized wind for all the organ, with the exception of the Solo Organ, is provided by a five horsepower electric blower in the basement of the house. Wind for the Solo Organ is provided by a two horsepower electric blower located in the attic. The console, located in the Great Hall, is controlled by 147 tilting-tablet stop keys and couplers and various push button controls. The entire mechanism weighs over 20,000 pounds. Yet, the instrument fits so perfectly into its environment and blends so well into the style of the house, that you hardly know it is there until you hear its melodious sounds.

Organs have always been expensive instruments. It takes a fairly settled and prosperous individual or community to purchase and maintain one. As the Callanwolde Guild has duly noted, organ restoration is an expensive matter too.

Mary Lynn related that on June 10, 1985, the Callanwolde Guild authorized a $23,000 contract for restoration of the Organ’s Swell Division. On December 15, 1986, the Guild signed a $42,000 contract for rebuilding, rewiring, and restoring the organ’s console. A state-of-the-art digital recorder was also added at that time. Afterwards, on October 23, 1988, the Callanwolde Guild authorized a $26,000 contract for repairs, pipe replacement, etc. on the organ’s Solo Division. In the Fall of 1989, the Guild signed a $20,000 contract for restoration of the Organ’s Echo Division.